Colonial Wars |

American Wars |

Link To This Page — Contact Us —

Belle Isle Prisoner of War Camp

Search, View, Print Union & Confederate Civil War Prisoner of War Records, 1861-1865

Confederate 1862-1864

Richmond, Virginia

Belle Isle seemed to be a great place to become a Confederate prison according to local officials. It was abundant in wildlife and had good geography. The island was used as a training and muster site at the beginning of the war. It was beyond the congestion of Richmond and was located near a fall line in the river where swift river currents would discourage escape attempts. A bridge that linked the island to the mainland could be easily guarded and was connected to the nearby Richmond & Danville Railroad, where prisoners and supplies could be easily supplied.

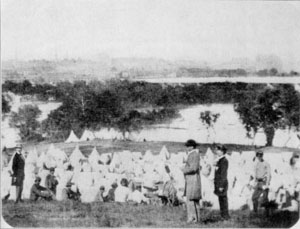

The place used for the prisoners was about 6 acres enclosed by an earthwork 3 feet high. This earthwork served as the deadline. The site was to be able to hold 3,000 prisoners, and was reached within 2 weeks after opening. The prisoners used tents for protection. They were assembled in a maze on the grounds.

In mid-June, authorities began taking Union noncommissioned officers and privates from all of Richmond's prison buildings and sent them to Belle Isle. In mid-July 1862, there were 5,000 prisoners on the island. The prisoner-exchange program was started by both sides. Prisoners were processed from Belle Isle through Libby Prison until the prison was nearly vacant. By September 23, the prison was closed.

In January 17, 1863, the prison was re-opened then closed until May, when it was opened again. By November, the prison population reached 6,300 prisoners. In February 1864, the Belle Isle prisoners were moved to a prison in Georgia. On February 7, prisoners began leaving in groups of 400 men. By March 1864, the last group of prisoners left Belle Isle. The following June, 6,000 men were confined here but they were all transferred out to Danville Prison and Salisbury Prison by late October.

During the 18 months the prison was operating, more than 20,000 prisoners were received at various times. Estimates have the death total at nearly 1,000 men. There were few known escape attempts at the prison. The prisoners who did manage to escape were presumed to have drowned in the river.

|

LIFE & CONDITIONS:

When the prison was reopened in 1863, the earthworks were increased to 5 feet high with ditches running along both sides. The inside of the prison was marked off with 60 streets radiating from a central avenue. The streets were lined with tents for the prisoners, with about 14 to 15 men per tent. There were enough tents for 3,000 prisoners. After the limit was reached, the additional prisoners were on their own. The guards also stayed in tents outside of the compound along with 5 hospital tents and a cookhouse constructed of wood.The river was divided into sections for different uses. The upper segment (10 feet)was used for drinking water, the next segment (30 feet) was for bathing, and the last segment (150 feet) was for the latrine.

With the lack of trees at the prison, the prison was exposed to the intense summer heat and the bitter winter cold. At first with the prison's first commandant, Capt. Norris Montgomery, prisoners were allowed to bathe in the river and buy additional foodstuffs from local sutlers. When Montgomery was replaced by Capt. Henry Wirtz (later to be the Andersonville Prison commander), the privaleges were stopped.

The prisoners passed their time in the same way as in other prisons. They played cards, chess, checkers, and crafts.

Accounts of living conditions at this camp vary. It went from the camp having good drainage, enough tents, and sufficient rations to it not having cruelly-used captives, inadequate facilities, and starving conditions.

Other accounts claim there were never enough tents on the "unhealthy" island, that prisoners slept outside on damp, boggy ground, and on one occasion several men froze to death. There is little doubt that, as shortages of food and supplies almost paralyzed the Confederacy and the number of prisoners grew, the captives suffered. At one time there were about 10,000 prisoners on Belle Isle.

A committee sent to the island by the U.S. Sanitary Commission reported being told the men were fed "mule meat and wormy, buggy soup" and some were so near starving as to devour a dog. A Union doctor who treated exchange prisoners confined at Belle Isle wrote that "every case wore upon it the visage of hunger, the expression of despair.....Their frames were, in most cases, all that was left of them."

After the war, a prisoner recalled Belle Isle as a "nightmare of starvation, disease, and suffering from cold."